A project in collaboration with the Maharaja Man Singh Pustak Prakash, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur, Rajasthan.

Maharaja Man Singh acceded as ruler of the princely state of Marwar (in present-day Rajasthan) in 1803, in what was an intensely contested fight for the throne. He attributed his ultimate, miraculous success to the intercession of the divine sage Jālandharanāth, of the Nāth lineage of yoga-practising ascetics. Man Singh was himself a devotee of the Nāth guru Devnāth, and during the forty years of his reign the Nāths enjoyed enormous power and influence in the kingdom, displacing the Brahmin religious establishment and Rajput aristocracy.

The Nāths, recognisable especially by the large hooped rings that pierce the cartilage of their ears, became influential in India from the thirteenth century, and often formed power alliances with kings. They were feared, and therefore valued, because of the supernatural powers they could unleash on enemies. The Nāths have become particularly associated with Haṭhayoga, and although contemporary Nāths practise little yoga they are nevertheless one of the most historically important lineages in its development and theorisation. Nāth haṭhayoga, broadly speaking, emphasises the attainment of immortality and supernatural powers, as preludes or alternatives to final, disembodied liberation—an emphasis suited to their often worldly concerns.

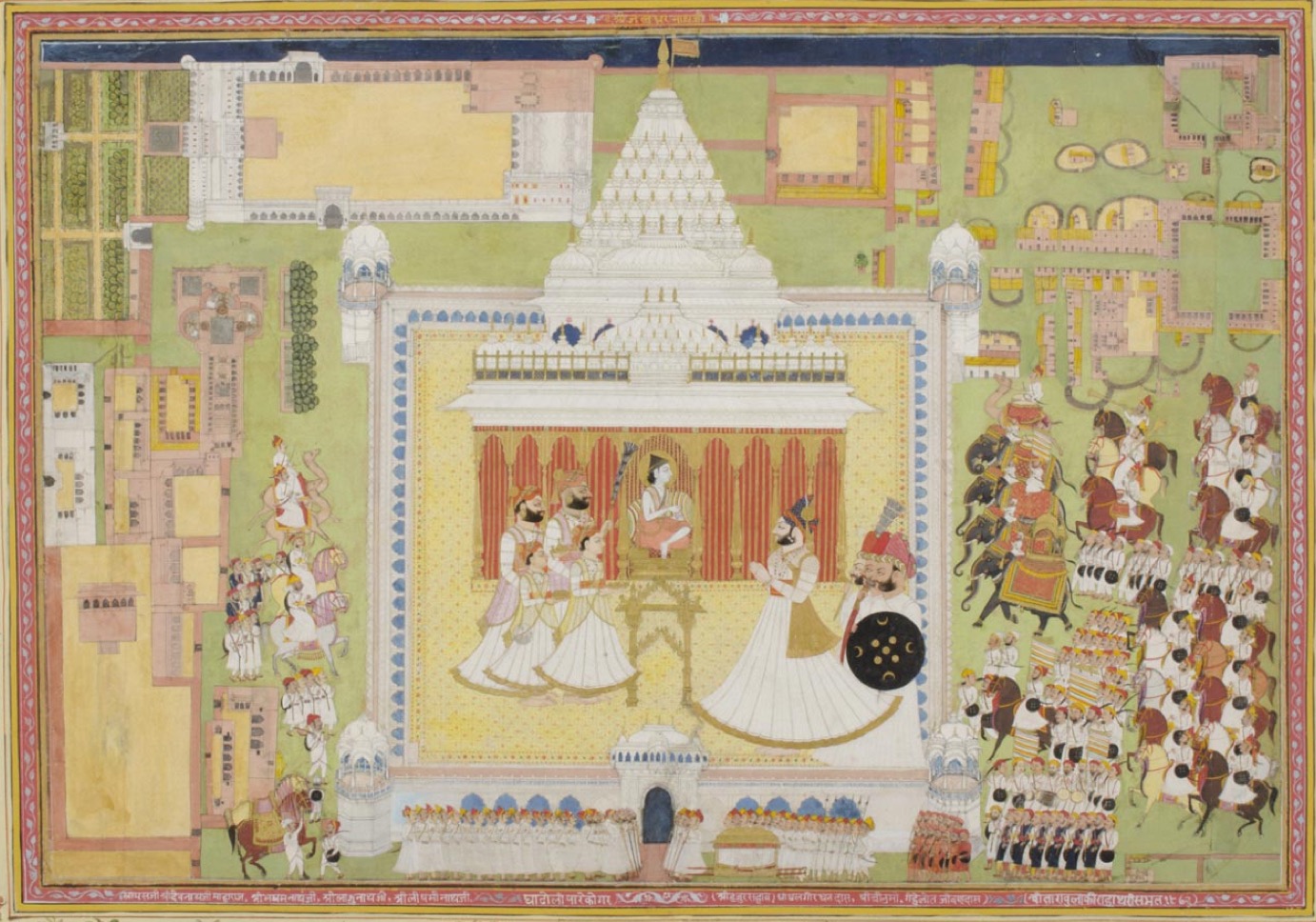

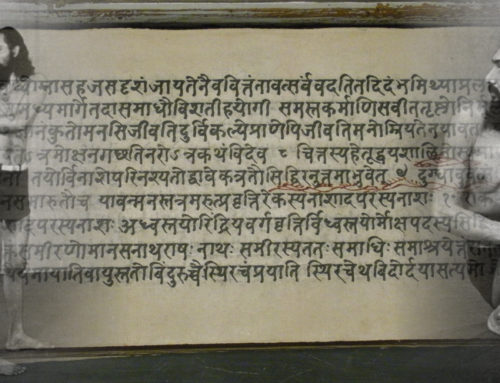

Mān Singh patronised the composition of new works on yoga and the Nāths, and the collection and copying of a large number of existing manuscripts on yoga and other topics. Many of these manuscripts are now housed in the Man Singh Pustak Prakash at the Mehrangarh Fort in Jodhpur. The collection is one of the most important in India and provides a snapshot of the state of development of yoga in northern India in the first half of the nineteenth century. Also vital in this regard is the fort’s immense art collection: many of the pieces from Man Singh’s artistically innovative reign contain yogic themes, and point to Jodhpur as a vibrant centre for the production and collection of knowledge about yoga. The nearby Mahāmandir, the centre of Nāth power in Jodhpur at the time, is itself a work of yogic art, best known for the murals of eighty-four āsanas (postures) in the main, central enclosure.

In collaboration with Dr. Mahendra Singh Tanwar of the Man Singh Pustak Prakash, and others at the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, we will attempt to trace the provenance of the collection’s many manuscripts and paintings on yoga through the detailed records kept by Man Singh’s administration. Many of the texts and artworks were gifts from other rulers across India, and some came from as far away as Nepal. By mapping the derivation of texts and images, and cross-referencing with what we already know about the development of yoga during this period, we hope to reconstruct a broad, detailed picture of yoga’s history in the first half of the nineteenth century, before the death of Man Singh, the dispersal of the ruling Nāths, and the arrival of the British as a significant power in Jodhpur.

This pilot project will, we hope, be the first in a serious of collaborations between the Haṭha Yoga Project (SOAS, University of London), and the Man Singh Pustak Prakash, under the aegis of the soon to be established Yoga Institute at the Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur.